Mark Tansey, "Coastline Measure," 1987, oil on canvas, 87 x 122 in. Click to enlarge.

Alumni engagement is amorphous, something we all struggle to define and measure. It's also something we urgently need to measure better to figure out whether we're successful, whether what we're doing works.

So—what should we measure? And how on earth do we measure it? Those are the questions we're all asking ourselves.

Traditionally, we've used metrics like these as proxies for engagement:

- Event attendance

- Event NPS ratings

- Chapter and board participation

- Volunteering

- Social media engagement

- Email open and click-through rates

- Giving rates

- "Engagement scores" algorithmically derived from the above data

Marquette University, for example, uses a 16-point model to measure engagement, where each data point is weighted to calculate a final score.

Their model is a good one. It uses over a dozen discrete, readily available data points, rather than chasing after the less tangible. Only Marquette's advancement team can say how accurate its final engagement scores are, but if we understand measurement as "any reduction of uncertainty," then Marquette is successfully measuring engagement. Marquette recognizes that no single data point is enough to represent alumni engagement, and that its engagement score is only a functional approximation.

It's when we aren't satisfied by approximations and instead seek absolute answers from a fuzzy world that we get into trouble.

For example, alumni networking plays a significant role in many institutions' engagement strategies. Alumni mentoring is also popular right now. But how do we quantify interpersonal interaction and its benefits? And what do we risk losing by quantifying the unquantifiable?

“Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted.”

To answer these questions, I'll borrow some terminology from political scientist James C. Scott. In his 1998 book, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed, Scott uses the term "legibility" to describe, in short, the degree to which information can be quantified and used by centralized organizations. Whenever we discuss whether or not something can be measured, we are having a conversation about legibility.

Much of Scott's book focuses on how governments have forced nomadic peoples to settle into sedentary communities in order to better regulate and tax them. (It's hard to collect taxes when your subjects keep moving around!) Of course, in doing so, those governments caused enormous harm to those peoples. In seeking to render its citizenry legible, governments inadvertently destroyed intangible, illegible value. Nomadic herding practices are far less environmentally destructive than sedentary pasturing practices, for example. When the Chinese government forced nomads in Inner Mongolia to settle onto fixed plots of land, it got its tax money but created harmful herding practices that ravage Inner Mongolian grasslands to this day. The Chinese government didn't see the value in nomadic herding because that value was illegible to them.

We risk causing similar harm when we seek to quantify the unquantifiable, to render legible the illegible, in our own work. To return to the example of alumni mentoring and networking, many schools implement strictly structured programs so that they can track participants, activity, and outcomes. We're tantalized by the prospect of neat spreadsheets and charts that track progress and ROI so that we know what we're doing right. It's natural to want that.

Tansey's painting offers a postmodernist critique of our urge to create order by measuring a fundamentally chaotic world.

But the moment we start designing for legibility, we stop designing for people. Networks and relationships are powerful educational and career advancement tools because they are flexible and can help alumni with an infinite variety of needs. Looking for a job? Find someone (who knows someone) who is hiring. Looking to move to a new city? Get advice from a fellow alumna who did the same thing a decade ago. Looking to switch careers? Talk to an alumnus five years your senior in your prospective industry.

Strictly regimented mentoring programs cannot solve these problems. Often, the only problem they do solve is our problem with measuring alumni interactions. One mentoring platform on the market limits mentor-mentee interactions to discrete, timed, one-on-one meetings. This makes them easily trackable, but almost entirely useless. Alumni don't build meaningful relationships in one-hour time slots.

Furthermore, a one-hour virtual meeting is not itself a mark of success. We might know that 14 such meetings took place during a given week, but would we know whether those meetings were successful? Whether alumni were hired or otherwise found what they needed? No. Those metrics are what are meaningful. When we optimize for what is legible—the one-hour meeting—rather than what is meaningful—the real-world outcome of those meetings—we get the illusion of progress when in fact we may be making none.

That illusion of progress not only prevents us from accurately measuring success, it leads us to design strategies and programs that are actually harmful to engagement in the long term.

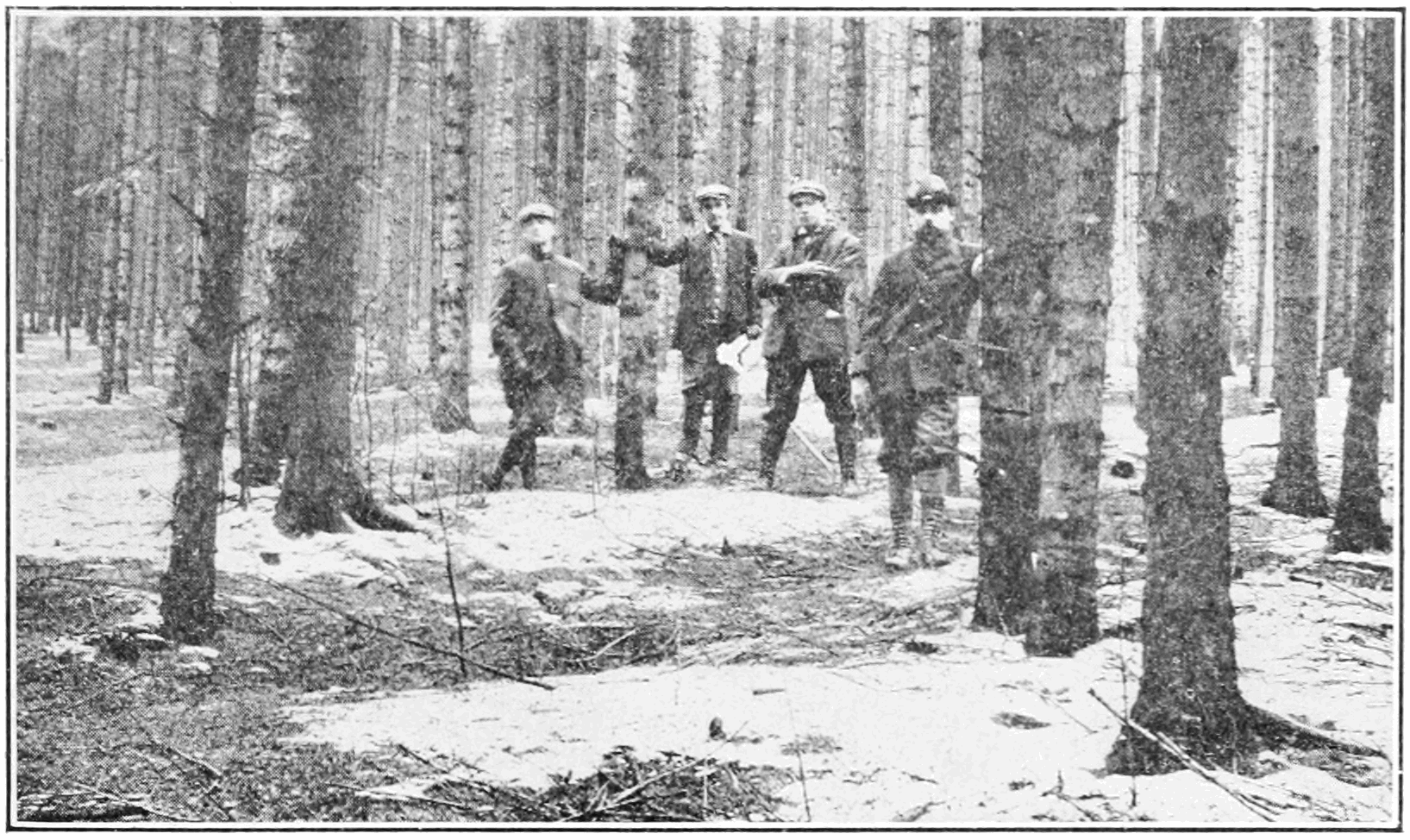

German foresters standing in a planted forest in 1913. Early German foresters planted neat rows of one or two species of trees to make it easier to keep track of and harvest timber. In doing so, however, they reduced biodiversity and made their forests more vulnerable to pests and disease. They also eliminated other trees and plants that had value to local communities for uses other than timber. When we focus only on making things legible, we risk sacrificing usefulness for legibility and doing long-term harm. (See Scott, Chapter 1.)

One now defunct alumni engagement app—the app's developer has gone out of business—experienced just this problem. The app was offered free to colleges and universities in an effort to drive widespread adoption. But when schools' alumni signed up, they found...

- A feature set limited to scheduling appointments with other users

- A desolate online community, because the vendor did not help schools build a network before signing up their alumni

- No reason to come back and keep using the app

Schools got decent adoption numbers because it was easy to install the app and sign up. They even got some nice looking stats on user-scheduled appointments. But, in reality, their alumni were signing up for the app, using it once, and then never using it again. Their appointments often never even occurred, and the app did not keep track of those that did or their outcomes. The app was designed to encourage users to do things that were legible, but not useful. That legibility was manufactured, not real.

Schools using the app saw the illusion of progress, but alumni were actually annoyed by their alma maters having cajoled them into signing up for something that was a waste of their time. Those schools that moved on and tried to get alumni to use something else often had trouble convincing alumni to do so because of the negative experience they had using the previous app. It left a bad taste in their mouths and damaged their trust in the alma maters.

This is just one example of engagement efforts that look good on the surface but are actually harmful to our relationship with our alumni. Other examples are everywhere. Any event, group, or program that sucks up our limited resources without generating real results is an obstacle to success. Vanity metrics prevent us from identifying these obstacles and overcoming them.

““Things are always as they seem? Since when?””

We are all tempted by easy access to data. But in our search for legibility, we must take care not to manufacture it. Measuring what is easy to measure is not measuring what is right. Rather than falling for illusory metrics, we should remember the real definition of measurement—that it is any reduction of uncertainty. Uncertainty can only ever be reduced, never entirely eliminated. ♦︎