Cracks are showing in our traditional methods for engaging alumni. Alumni giving is down, fewer and fewer think their degrees were worth the cost, and they aren't giving for the same reasons. The fundraising landscape is changing, and so are expectations of and perspectives on higher education.

In times of change like these, it's important that we examine—and challenge—our core assumptions.

So today we consider the funnel.

The engagement funnel, that is. You use it every day, even if you aren't familiar with it. In marketing circles, the funnel is ubiquitous. It looks like this:

The metaphor of the funnel is simple: You start with a broad but shallowly engaged audience and winnow your way down to folks who are most likely to be interested in whatever it is you're selling. Then you sell it to them.

The traditional engagement funnel for advancement and alumni relations is similar, though it ends with a gift (or gifts) rather than a purchase. We have come to understand engagement as the process, represented by the funnel, of shepherding alumni toward making gifts.

Each step in the funnel excludes people who aren't ready or willing to participate in the next one. An alumnus might be ready to attend a reunion or chapter event, but not to make a major gift. In these cases, it's the gift officer's job to figure out who is most likely to "convert," who to invest time in and who not to.

The funnel, by definition, winnows the majority of people out. They're willing, engaged participants, but fewer and fewer people are ready to take each successive step as the asks get bigger. The more we ask of our alumni, the fewer there are who can answer.

It's an inherently exclusive, extractive process.

We, the rational economic actors that we are, invest the most resources where we see the most returns. And right now the biggest returns are at the bottom of the funnel: well established alumni with strong affinity for their alma maters. Consider the size of our annual fund staffs and compare that to how many gift officers we have. Gift officers give the most promising prospects personalized attention from a human being. Everyone else receives relatively generic communications from the institution. Per capita, the wealthiest alumni receive far more attention than the rest.

And the rest of our alumni are often resentful that we ask them for money at all. (See our recent post, "Why do we treat our new alumni so poorly?") For alumni who feel ignored, even the smallest ask is a big one.

We give our students loads of attention. We give our established alumni loads of attention. But we practically ignore the alumni in between. They want to be better connected with their alma mater, more a part of their old community, but we don't spend time on them because we don't see them for everything they have to offer.

What if we recognized the value of ends other than financial giving so we could invest in processes that include more people over time, rather than ones that winnow them out?

Ron Cohen, vice president of university relations at Susquehanna University, explains:

Most alumni have far greater value to give their alma mater than the checks they write, or what wealth screenings might find. The value comes via the lives they lead, the talents they’ve acquired, the enthusiasm they maintain for their own undergraduate experiences, and their strong inclination to pass along what they know. Their powerful, personal stories can generate a larger network for an institution in ways other than a direct financial gift from that alum. Advancement staff can and should be harvesting this type of value.

Ron gives the example of a recent graduate who spoke enthusiastically about his alma mater to prospective students, resulting in about 20 applications. After some back-of-the-napkin calculation, Ron estimates that that alumnus's recommendations alone generated hundreds of thousands of dollars in revenue for his alma mater. We all know of alumni who have similarly given back to our institutions in ways other than making direct gifts. They give career advice, hire, and help students and their fellow alumni. These actions account for millions of dollars in value provided to our communities—and our institutions.

To Ron's suggestion that schools harvest this kind of value, we would add that they should also cultivate it. By cultivating it, we build giving capacity rather than just boosting giving totals in the short-term. We flip the funnel on end and replace it with something that generates value, rather than just extracting it.

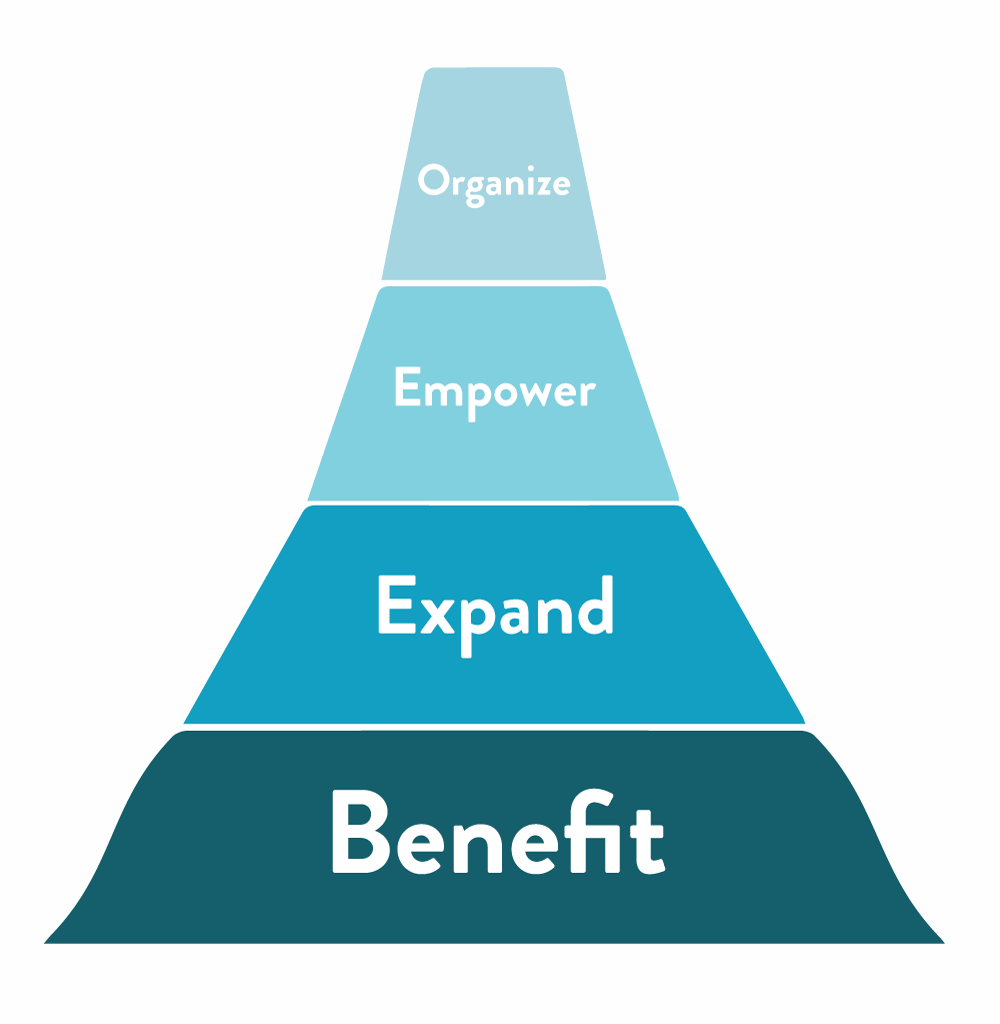

Building alumni career communities is one example of such a process. Schools start by organizing a core of handpicked alumni who are experts in their field. They empower those alumni to build industry-centric networks. They help those networks expand. And when those networks grow and can meet the needs of thousands of students and alumni, schools help their constituents reap the benefits.

This differs from the standard engagement funnel in that it seeks to include more people over time rather than excluding them. It meets the needs of our constituents by connecting them with one another, while simultaneously cultivating giving capacity by helping them advance their careers. It makes people happy and makes them more viable participants in the traditional engagement funnel in the long-term.

The funnel is, of course, just a metaphor. We can't take all our processes and flip them on end. What we can do is find and commit to strategies that expand our networks and strengthen our communities. ♦︎