Mark Tansey, Action Painting II, 1984. Oil on canvas

Cold Data: The Status Quo

“Cold data” is data as we know it: quantitative metrics that capture a single variable at a time, at a single point in time.

Grades. Retention. Giving rate. Net Promoter Score. And so on.

We use metrics like these all the time to keep track of how we are doing, how our institutions are doing, and how our constituents are doing. These metrics can be powerful! There’s no denying that.

But metrics like these have their limitations, too. Two big ones come to mind for me. First, these data are narrow in scope—they tell us one thing and lack context. Second, these data don’t tell us why—why did a student fail that class, why did they drop out, why didn’t they make a gift? These limitations are what make these data “cold.”

When institutions bump up against these limitations, their traditional response is to gather more cold data. If we’re unsure why the NPS for an event was low, we measure more specific things—did you dislike the food, did you dislike the people, did you dislike the venue? When retention rates drop, we ask the same sort of questions—on a scale of 1 to 10, to what extent was it X, Y, or Z?

But these questions have the same weaknesses our first one did! What if it isn’t X, Y, or Z that’s the problem and we aren’t even asking about the right things? What if the problem is too complex to convey with a few answers on a ten-point scale? What if one of the variables we measure scores low but is actually a red herring distracting us from the real issue?

The solution to the limitations of cold data is not to gather more cold data. It is to collect a different sort of data altogether.

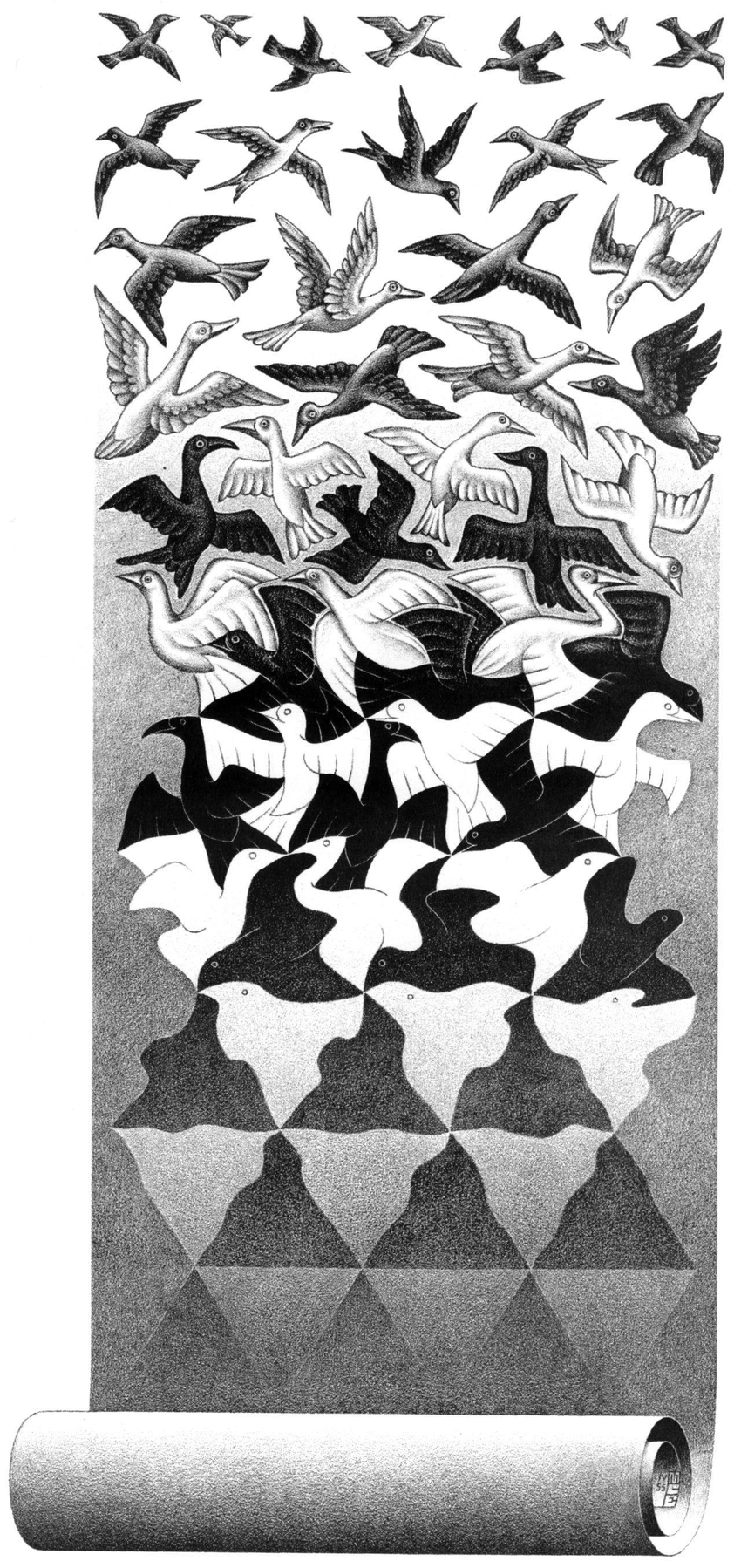

M.C. Escher, Liberation, 1955, Lithograph

Warm Data: An Alternative

In short, warm data is data that isn’t cold.

I borrow the term from Nora Bateson, a writer and filmmaker who likes to tackle complex ideas and systems. In her 2017 piece, “Warm Data: Contextual Research and New Forms of Information,” she offers her vision of warm data: “‘Warm Data’ can be defined as: Transcontextual information about the interrelationships that integrate a complex system.”

To which I respond: 🤔. It’s a little too academic for me. Fortunately, Bateson is a little more clear in this interview that’s on YouTube:

“The more I was thinking about big data, the more suspicious I became of having information that was derived by pulling things out of context and not putting them back in context… Warm data became a term to hold space for that idea that there could be another kind of information that would augment and work with the existing notions of data that are taken by getting things out of context. So we can have decontextualized, specific, detailed data and have another thing, warm data, that would give us the information about how the system is working. Why is it being the way it’s being? How is it functioning in its larger set of relationships?”

When I think of information that is in context, that captures the complexity of a whole system, and that can convey ambiguity, I think of one thing: stories. Stories capture the “why” that cold data don’t; they capture the tangle of relationships in a system. To me, “warm data” means stories.

And by story I don’t just mean “This variable changed from Y to Z.” By story, I mean the narratives we use to make sense of our lives, told by the people who live them.

The student experience seen through cold data is entirely numerical: This many students got these grades; this many students dropped out; this many students graduated into alumni who gave back to their alma mater. Understood with warm data, the student experience is complex: This student got high marks and graduated on time, but always struggled to make ends meet and never felt supported or understood by their alma mater, so they don’t make gifts now as a result.

Cold data are narrow in scope. Warm data—stories—give us the bigger picture. They reveal things we can’t see and things we can but don’t expect. They also get us to the “why” of the problem.

And here’s maybe the best thing about warm data: You don’t have to be a statistician to collect them, interpret them, or apply them. Anyone can learn how to collect stories from their constituents, how to understand them in context, and how to use them to make change and solve problems. Gathering warm data for this purpose is also much less resource and time intensive than gathering cold data.

Warm Data in Action: Alumni Sentiment at Northern Michigan University

This spring, we worked with the alumni relations team and at Northern Michigan University to evaluate the effectiveness of their current alumni engagement strategy and to revise it accordingly. They had also recently transitioned to working under NMU’s advancement office and needed to ensure their revised strategy fit the new reporting structure.

The NMU team knew that the best way to evaluate the effectiveness of their alumni engagement strategy was to go straight to their alumni and ask them about their relationship with their alma mater and their satisfaction with the institution’s alumni outreach.

In the past, NMU had conducted a variety of alumni surveys, most recently a quantitative survey of recent graduates—cold data. This time around, we trained NMU’s alumni team and alumni board to conduct empathy interviews of alumni and gather warm data.

With just two dozen alumni interviews, NMU was not only able to obtain a demographically representative sample of its alumni body’s, but also identify the similar patterns in alumni sentiment as they found with over 1,000 quantitative survey responses. They also collected new information about how they could do better.

Where cold data are information-poor, warm data are information-rich. It took just over 20 short alumni phone interviews for NMU’s alumni team and alumni board to identify specific parts of their engagement strategy that they could work to improve. Compare the week it took to put those interviews together with the months and thousands of dollars it takes to conduct an alumni survey and you’ll immediately see the appeal of this approach.

Collecting warm data was a much more time- and resource-efficient way for NMU to gauge alumni sentiment, and the process of interviewing alumni also allowed the NMU alumni relations team to involve the alumni board in the process directly. This meant they had stakeholder buy-in from day one and were ready to act on their findings as soon as they had them in hand.

Warm Data at Your Institution

Collecting warm data is easy—you just have to know how to ask the right questions. The collection process, also known as empathy interviewing, is a foundational part of design thinking. If you are interested in using warm data at your institution, we recommend checking out these resources on conducting empathy interviews:

“How to Conduct Empathy Interviews,” Taylor Birchall, Zion & Zion

“Interview for Empathy,” Stanford Design School

Starting this fall, we will be offering a digital Toolkit for Change which will provide you with videos, worksheets, and a curriculum on how to begin listening to your constituents as we’ve outlined in this blog post. If you’re interested in it, click here to get our one-page PDF outline about it or email Director of Marketing & Product Kieran Hanrahan for more information.