Last month, we launched the Wheelwomen Switchboard—a Switchboard for cyclists who identify as women nationwide. (You can read more about it in the Oregonian and BikePortland.) Since its inception, dozens of wheelwomen have posted asks and offers, and logged successes. This is just one of those success stories.

Josie posted an Ask on the Wheelwomen Switchboard a few weeks ago looking for people to interview for her blog, Life on Two Wheels. Josie uses her blog to chronicle her own adventures in the bike world, but also as a place for other cyclists to share their experiences. “My hope is that the stories will inspire others to get on a bike,” Josie says.

Josie’s Ask has led to two interviews with other wheelwomen so far: Emily, from Marin County, California, and Whitney from Seattle.

Josie says that the Wheelwomen Switchboard makes it easy for her not just to interact with other like-minded wheelwomen, but to inspire members of the community in turn. “I’m somewhat shy in real life, but online I’m much more outgoing,” she says. “It’s been very positive to ‘meet’ new people and make new friends. The stories that I’ll be sharing (and have shared) are really great and I hope will inspire other people as much as they have inspired me.”

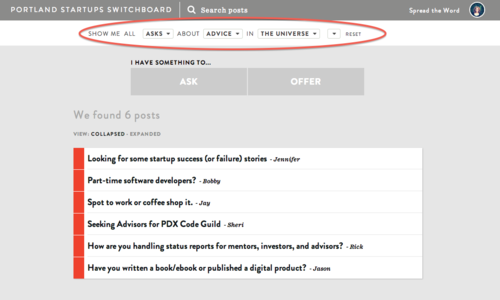

For Josie, Switchboard’s strengths are its simplicity, its scope, and its ability to bring members of a loosely connected community together. “It was easy to step into and use. Not only getting responses but finding other topics to chime in on,” Josie says. The Wheelwomen community is spread out across the country and bound together only by its members’ mutual love of biking. Switchboard gives its members a place to connect in collaborative, meaningful ways. “The bike riding community isn’t just in ‘one town’ but it’s all over. Everyone has something they can bring to the table and share!”