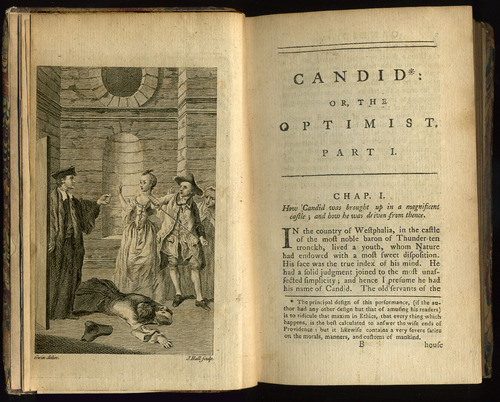

Are you familiar with Candide? I recently read it for class and have been thinking about the last line of the novella ever since.

Candide first, then social media.

At the end of the novella, Candide, the titular character and protagonist, finds a home far away from his original home in Germany and converses with his old tutor, Pangloss. Pangloss, an ‘optimalist’ who believes that all is always for the best, vindicates Candide’s past misfortunes:

"There is a concatenation of all events in the best of possible worlds; for, in short, had you not been kicked out of a fine castle for the love of Miss Cunegund; had you not been put into the Inquisition; had you not traveled over America on foot; had you not run the Baron through the body; and had you not lost all your sheep, which you brought from the good country of El Dorado, you would not have been here to eat preserved citrons and pistachio nuts."

Candide spends the entire novella trying to reconcile Pangloss’s optimalism, which he believes in so thoroughly as to appear brain-washed, with all the woes that befall him. Now, however, rather than agree whole-heartedly with Pangloss’s assertion, Candide only answers:

"That is well said, but we must cultivate our garden."

After blow upon bruise, Candide altogether renounces theorizing and philosophy—Pangloss’s or otherwise. He is done with circular reasoning. He will pay attention to that which is before him. He will cultivate his garden.

Now the volta from Voltaire to social media.

Ostensibly, social media enables us to connect with one another. Even if you only buy the origin story advanced by The Social Network, in which Harvard students join Facebook merely to see who is single and who isn’t, Facebook began as a platform for connecting with other people. It was a glass in which the reflections of others (their profiles) directed us to them in the real world.

Soon, the “like” trumped the relationship as the basic unit of Facebook. As people paid our profiles attention and showered us with likes, the glass in which we saw the reflections of others shifted just enough for us to glimpse our own. We were enthralled. We turned from the real-world garden of relationships to our online identities.

As Pangloss seeks to explain the world with theory, we sought to explain ourselves with our profiles. Pangloss reduces the complexities of the world to the motto “All is for the best”; we quantified our self esteem with likes, followers, retweets, notes, and so on.We forgot that social media is about relationships, not profiles.

That’s why, on Switchboard, your profile is your past post history and nothing more—no likes, no followers. Check my profile and you might find that I posted an offer to host people in Maine, or that I asked for advice about finding a job at the Spacing Guild. The only potential action you can perform in response to my profile is contacting me to fulfill my ask or take me up on my offer. There is no intermediate “like” or “follow.” Switchboard is useful. Human. You are not directed to interact with my online persona, you are directed to interact with me.

Like Candide through most of Candide, social media has lost its way. Our online profiles beguile us, and we forget our real relationships and our real selves. But no matter how much detail I add to my Facebook profile, my Facebook profile will never be me. My Facebook friendships with my friends’ Facebook profiles will never be my real relationships. We cannot explain ourselves, only become ourselves.

We must cultivate our garden.