As a former higher education career services administrator now working in edtech, I’m concerned to see institutions sourcing technology solutions without an understanding of the biases that exist in that industry. It’s important for higher ed leaders to assess whether they are sourcing technology through an equity lens and understand how those decisions perpetuate inequality.

(For those of you short on time, I have included a checklist that your technology sourcing committees can use to evaluate partnerships as an addendum below.)

I started to grow concerned after returning from the ASU+GSV conference (Arizona State University + Global Silicon Valley Capital, a venture capital firm) this spring. True to its name, the conference attracts education thought leaders, edtech companies, investors, and foundations to discuss the challenges facing education and forge partnerships to solve them.

Imagine a vendor hall full of products, like the ones you might see at a CASE or NACE conference. Each of these technology solutions is designed by a team of founders. That team brings their life experience and perspective to the product they have created. Like a chef at a restaurant, the food is a reflection of their training and point of view. If we don’t have a diversity of founders, that means we don’t have a diversity of solutions, we just have a long menu of the same dish. Higher education can’t afford a monoculture. We desperately need diverse founders and diverse solutions to mirror the ever-changing demands of first-generation and low-income students.

Unfortunately, that’s not who is currently being rewarded in the existing venture capital structure that funds these businesses. Many of my peers in higher education might not know, as I didn’t until working in this industry, that only 2 percent of venture capital dollars go to women founders. Yes, that statistic is true in 2018. If you are a woman of color, it’s less than 1 percent.

Many of these founders understand better than anyone the barriers to economic mobility that exist for the majority of college students and alumni today. And yet the inequality in funding prevents their solutions from broadly going to market and being in that vendor hall in the first place.

The promise of higher education is to deliver equal access and mobility, but the existing technology solutions are not always founded by teams with those same principles. When institutions do not source technology with equity in mind, they unknowingly perpetuate the exclusive, inaccessible venture capital culture of Silicon Valley. Many institutions are trying to solve complex organizational challenges that impact the future economic mobility of their students and alumni. But the market excludes the very entrepreneurs who know how best to serve the most vulnerable and fastest growing constituent populations.

We face this predicament because a business model of rapid growth does not align with the mission of economic mobility in higher education. Venture-backed, once-in-a-lifetime growth companies (called “unicorns” because they are so rare) are focused on user acquisition, not user success. Their aim is to get as many users to sign up as possible, “disrupt” the industry, and then “exit” by selling themselves to the highest bidder and returning a hefty profit to investors. This creates a conflict: The product is designed for customer and user adoption, but institutions buying it need to deliver on institutional and user success.

The marriage of these two forces—products designed by a majority of white men that do not solve for community needs—has reached a crisis. We must question this process and do better. Institutions. We can start by listening to their community’s needs and choosing solutions designed by companies and teams that know how to meet those needs. The technology industry can start by being more inclusive to people who better understand them.

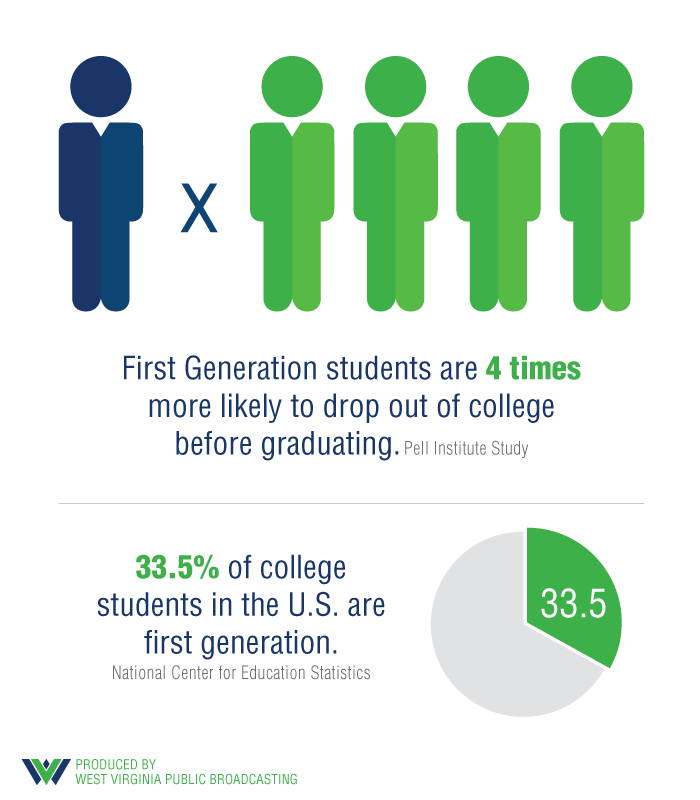

Institutions are struggling to meet the growing needs of their changing student populations. First-gen, low-income students (many of whom are students of color) face the most and highest barriers to economic mobility as they navigate their college education and postgraduate professional development. I hear from former colleagues in student affairs that they feel like case managers. They are scrambling to meet the basic needs impeding their students’ success: childcare, paying rent, even just getting enough to eat. These leaders are exhausted. Yet better designed technology can help them meet these needs at scale.

In turn, these needs teach us how edtech can do better. As a company, we at Switchboard learn every day how we must grow and change as a company. In some of our early partnerships, we could have done better to insist that institutions listen to the community first before adopting a tool. We have worked with institutions that cannot or are unwilling to invest in innovative processes in addition to adopting a new platform. Now, we only partner with institutions that are willing to invest in systems and software. We want to be a partner, not a vendor, and do the difficult work that is a necessary part of true innovation.

As a direct career services provider for over a decade, the majority of my work was focused on listening to thousands of students and alumni from various segments of student populations and at a variety of institutions: Portland State University, Clark College, Wingate University and Johns Hopkins University. I was also the first person in my family to navigate a traditional college experience. I know firsthand how difficult it is to complete a degree and transition into the working world without a robust network of professionals to open doors or offer support.

At Switchboard, we create products and services that listen to and meet the needs of the students and alumni who face challenges like the ones I did when I was in school. We help institutions build the network, increase support, and circulate opportunities necessary to create broader economic prosperity. Companies like ours must hire employees who have experience in education and who represent the populations of students who need the most help. We partner with institutions to innovate new systems and repair outdated ones. And, most critically, these solutions must be built by and with the communities we aim to serve.

Below is a suggested framework you can work into RFP criteria and your vendor selection process for sourcing vendors and technology with an equity lens. Career services and alumni engagement teams are incredibly under-resourced. We know every dollar counts for those teams, and every dollar wasted on an ineffective or ill-matched product is a dollar that could have supported a student or alumna who needed it.

This list is designed to help teams learn more about the founders, motivation, and business model a potential vendor and ensure that the product is a fit for the needs of their institution, students, and alumni.

Questions for the vendor

1. Who are the founders? What is their story?

2. What is the company's mission?

4. What segment of the student and alumni population was the product built to serve? Was it built in consultation with that target demographic to meet their demonstrated needs?

3. What student and alumni needs does it meet? What departmental and institutional needs does it meet? Is meeting that need a valid measure of success, or just a vanity metric?

4. Does the company offer services and account management to ensure processes are in place for the product to thrive? This should be evident beyond a customer help center and chat support offering.

5. What does success (or projected success) of their product look like in two to three years? What is their projected user participation and success rate over time?

6. How does the product produce ROI for your team and institution?

7. Who has invested in the company? What is company’s growth trajectory? Are they planning an exit or in it for the long haul? What is the company’s business model? How do they make money and what is their long-term plan?

8. Does their front facing team understand the needs of your team, students, and alumni?

9. How large is their team and how many institutions do they serve? What is the ratio of account managers and support engineers to institutions?

10. Can they share a copy of the product roadmap for the next 6 to 12 months? What percentage of developer hours are devoted to building solutions for the needs of their clients as they emerge?

Questions for you and your team to ask yourselves:

1. Have we listened to needs of students and alumni who we are not reaching with our current service offerings?

2. What needs are we meeting with this technology investment? Could those needs be met with any other existing technology solution we have?

3. How does this technology work to scale our strategy to meet those define needs?

4. What does success look like ? What metrics matter to evaluate success (should come from strategic plan), and is this technology solution mapping to those metrics?

5. Do we have FTE and resources to devote to the technology implementation/optimization?

6. Have we built cross-campus partnerships with teams who also see value in this solution and have resources to support us?

7. Are student and alumni leaders and community members a part of the implementation process?

8. Are we partnering with a technology provider that understands the emergent needs of students and alumni?