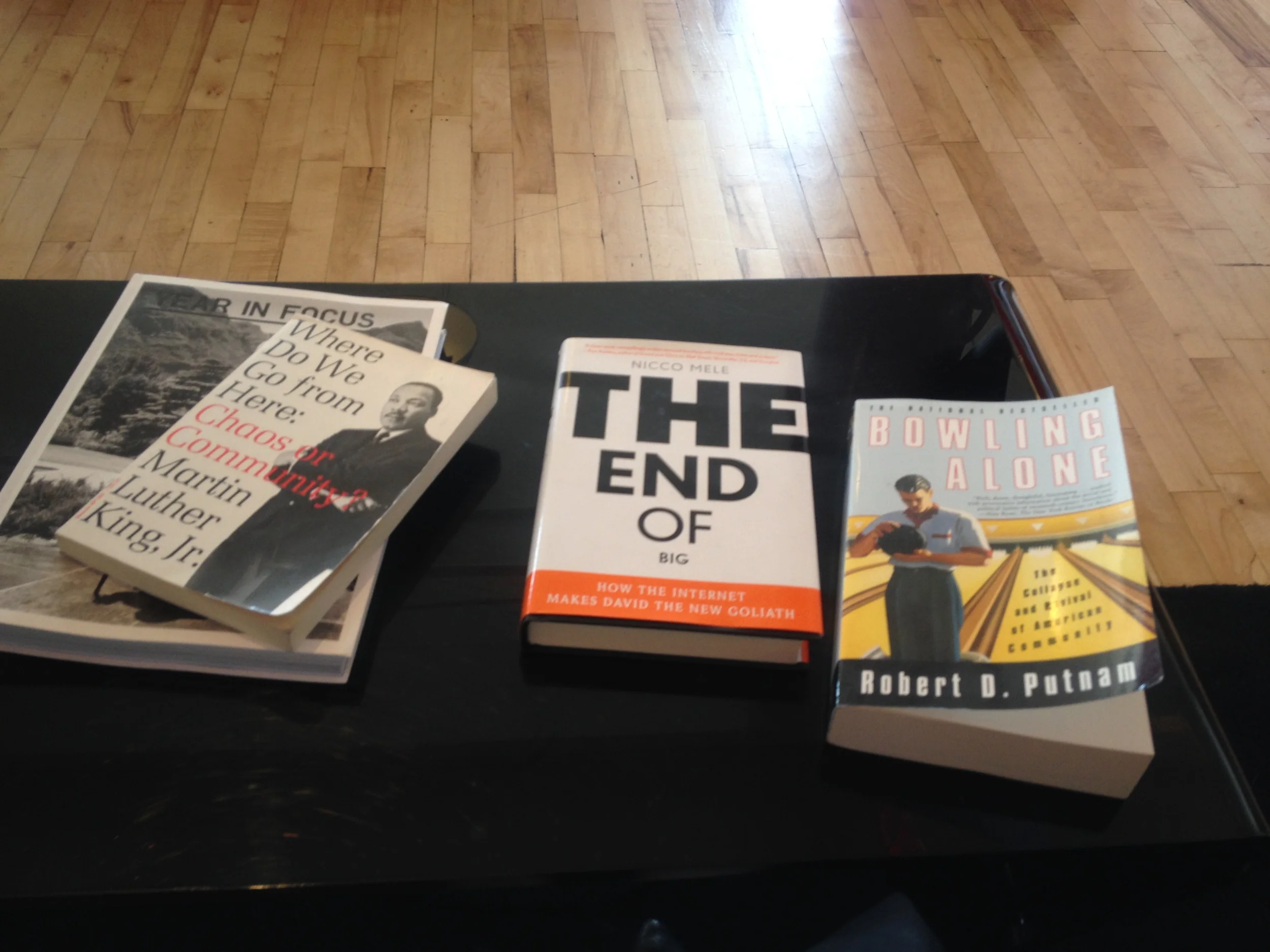

Last summer I had the good fortune of meeting Scott Heiferman, CEO of Meetup and kindred spirit when it comes to evangelizing the power of offline community. As I sat in a New York office nervously awaiting the meeting of someone I very much look up to, I flipped through Martin Luther King Jr.'s Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community. Today seemed like a good day to revisit it.

In the opening chapter, King quotes then-Assistant Director of Lyndon Johnson's Office of Economic Opportunity, Hyman Bookbinder, who said this in 1966 about combating poverty: "[U]nless a 'substantial sacrifice is made by the American people,' the nation can expect further deterioration of the cities, increased antagonisms between races and continued disorders in the streets." This notion of effort and sacrifice has been on my mind lately.

Not long ago someone posted a hopeful ask on the Switchboard for Reed College, my alma mater. An alumnus, Aidan, was going to be out of town and needed someone to drive his car to the mechanic. Without giving the logistics much thought, and despite Aidan's being a complete stranger, I volunteered to help him. The day arrived and, due to unfortunate and unforeseen circumstances, I was at the deathbed of a dear friend in Canada. But not delivering on my promise was not an option. I called on my saintly husband, who took a bus to fetch the car, drove the car to the mechanic, and took a bus home. He spent two hours of his day helping a stranger.

And that only scratches the surface of the effort required to build the community that King envisioned and Bookbinder alluded to. That effort can't just be for the people who went to the same college; it has to extend many circles beyond that. It isn't a retweet or the signing of a petition. Getting on a bus and schlepping across town to actually help with something is a step in the right direction, though a small one.

King presents a sketch of what is required of us in the final chapter, called "World House." Please go read it.

In it King describes the coming tide of technological innovation, the one we live in five decades later, but warns about mistaking technology for the deeper structure of common cause it must create. "Automation and cybernation will make it possible for working people to have undreamed-of amounts of leisure time. All this is a dazzling picture of the furniture, the workshop, the spacious rooms, the new decorations and the architectural pattern of the large world house in which we are living." Technology is ornamentation, not the house itself. "The large house in which we live demands that we transform this worldwide neighborhood into a worldwide brotherhood. Together we must learn to live as brothers or together we will be forced to perish as fools."

King quotes theologian Abraham Mitrie Rihbany: "You call your thousand material devices 'labor-saving machinery,' yet you are forever 'busy.' With the multiplying of your machinery you grow increasingly fatigued, anxious, nervous, dissatisfied. Whatever you have, you want more; and wherever you are you want to go somewhere else... your devices are neither time-saving nor soul-saving machinery. They are so many sharp spurs which urge you on to invent more machinery and to do more business." I could not think of a better way to describe all of the technology we've built that operates on the model of creating attention economies but that lacks the capacity to heal or meet basic needs.

And then, well, I'm going to let King take it from here:

"From time immemorial men have lived by the principle that 'self-preservation is the first law of life.' But this is a false assumption. I would say that other-preservation is the first law of life. It is the first law of life precisely because we cannot preserve self without being concerned about preserving other selves. The universe is so structured that things go awry if men are not diligent in their cultivation of the other regarding dimension. “I” cannot reach fulfillment without “thou.” The self cannot be self without other selves. Self concern without other-concern is like a tributary that has no outward flow to the ocean. Stagnant, still and stale, it lacks both life and freshness. Nothing would be more disastrous and out of harmony with our self-interest than for the developed nations to travel a dead-end road of inordinate selfishness. We are in the fortunate position of having our deepest sense of morality coalesce with our self-interest.

But the real reason that we must use our resources to outlaw poverty goes beyond material concerns to the quality of our mind and spirit. Deeply woven into the fiber of our religious tradition is the conviction that men are made in the image of God, and that they are souls of infinite metaphysical value. If we accept this as a profound moral fact, we cannot be content to see men hungry, to see men victimized with ill-health, when we have the means to help them. In the final analysis, the rich must not ignore the poor because both rich and poor are tied together. They entered the same mysterious gateway of human birth, into the same adventure of mortal life.

All men are interdependent. Every nation is an heir of a vast treasury of ideas and labor to which both the living and the dead of all nations have contributed. Whether we realize it or not, each of us lives eternally “in the red.” We are everlasting debtors to known and unknown men and women.

When we arise in the morning, we go into the bathroom where we reach for a sponge which is provided for us by a Pacific Islander. We reach for soap that is created for us by a European. Then at the table we drink coffee which is provided for us by a South American, or tea by a Chinese or cocoa by a West African. Before we leave for our jobs we are already beholden to more than half of the world.

In a real sense, all life is interrelated. The agony of the poor impoverishes the rich; the betterment of the poor enriches the rich. We are inevitably our brother’s keeper because we are our brother’s brother. Whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly.

This blog post will get digested into a Tweet. The Tweet, and the post, do nothing at all to act as our brother's keeper. These distribution methods are, as King would describe them, fundamentally "cheap." That is why we built Switchboard. We're aiming for outcomes that are less cheap but far greater. We want to help people build communities and enrich each other's lives.

As I am sure Scott, and anyone else committed to bridging offline and online communities, will attest, this is difficult, time-consuming work. We say so when you request a Switchboard: what you're about to undertake might require 10 hours of work in the first month. It isn't achieved with likes and endorsements. We repair the car, save the family farm, and find the homeless student a place to stay through effort and sacrifice. Only then can we say with any certainty that we're building the house, not simply decorating it.