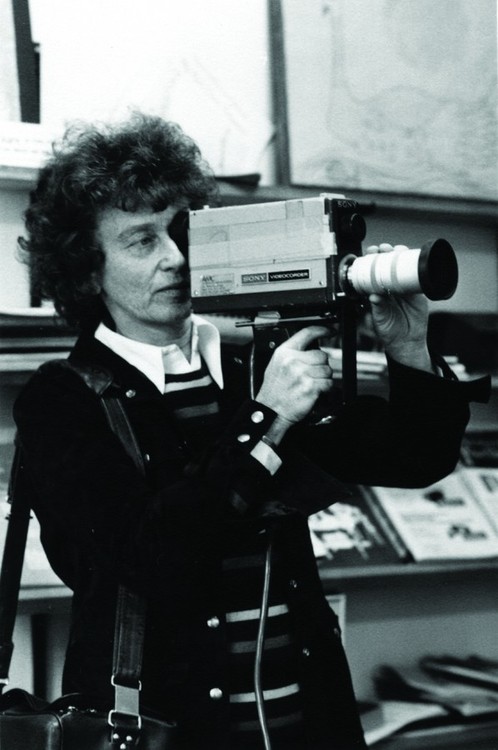

I’d like to take a moment and remember Red Burns, co-founder of NYU’s Interactive Telecommunications Program. She died last month.

In her opening remarks to new students she outlines her hopes for them. They read like commandments for what we are trying to do at Switchboard: “That you make visible what, without you, might never have been seen. That you are not seduced by speed and power. That you don’t see the world as a market, but rather a place that people live in — you are designing for people, not machines.”

Let’s just say that this is not the prevailing mantra of the start-up world.

Red’s name should be as familiar to us as Steve Jobs’. But had it not been for a friend of mine, I never would have known about her.

I went to Columbia Journalism School at the same time my friend Greg Borenstein started ITP. I’d make my way down to his building during the rare moments I could steal away from the Upper West Side. I’m not sure if it was like “Kindergarden for adults.” To me, it was what I hoped the future should look like. J-school was thinking and writing and words. ITP was thinking and action and stupendous failure and delight. And sometimes fire, spray foam, and miniature chairs. I’d find any excuse to stop by.

One time I was asked to wear knit gloves and assume a downward dog yoga pose. I looked up and the pressure from my hands had created a painting on the screen. During one of their bi-annual shows I donned a pair of glass headphones. The music came from live crickets housed inside. That was the year ping pong balls played instruments And Greg built Face Fight in which opponents struggle for control over the line of a digital drawing tool. The open loft was a riot of art supplies, Arduinos, soldering irons. I seem to remember trash bags full of cotton bunting. I once gained an audience with Clay Shirky but was too distracted by the resemblance of his office to a hardware store to fully pay attention.

If ever you succumb to a moment of pessimism about technology, peruse the projects from past ITP shows.

All of this came about because of Red, whose presence seems to guide every effort at ITP. It is worth printing all of her remarks, taken from ITPer Margaret Stewart’s fantastic remembrance in Wired.

From Red Burns’ Opening Remarks to New Students

What I want you to know:

That there is a difference between the mundane and the inspired.

That the biggest danger is not ignorance, but the illusion of knowledge.

That any human organization must inevitably juggle internal contradictions — the imperatives of efficiency and the countervailing human trade-offs.

That the inherent preferences in organizations are efficiency, clarity, certainty, and perfection.

That human beings are ambiguous, uncertain, and imperfect.

That how you balance and integrate these contradictory characteristics is difficult.

That imagination, not calculation, is the “difference” that makes the difference.

That there is constant juggling between the inherent contradictions of a management imperative of efficiency and the human reality of ambiguity and uncertainty.

That you are a new kind of professional — comfortable with analytical and creative modes of learning.

That there is a knowledge shift from static knowledge to a dynamic searching paradigm.

That creativity is not the game preserve of artists, but an intrinsic feature of all human activity.

That in any creative endeavor you will be discomfited and that is part of learning.

That there is a difference between long term success and short term flash.

That there is a complex connection between social and technological trends. It is virtually impossible to unravel except by hindsight.

That you ask yourself what you want and then you work backwards.

In order to problem solve and observe, you ought to know how to: analyze, probe, question, hypothesize, synthesize, select, measure, communicate, imagine, initiate, reason, create.

That organizations are really systems of cooperative activities and their coordination requires something intangible and personal that is largely a matter of relationships.

What I hope for you:

That you combine that edgy mixture of self-confidence and doubt.

That you have enough self-confidence to try new things.

That you have enough self doubt to question.

That you think of technology as a verb, not a noun; it is subtle but important difference.

That you remember the issues are usually not technical.

That you create opportunities to improvise.

That you provoke it. That you expect it.

That you make visible what, without you, might never have been seen.

That you communicate emotion.

That you create images that might take a writer ten pages to write.

That you observe, imagine and create.

That you look for the question, not the solution.

That you are not seduced by speed and power.

That you don’t see the world as a market, but rather a place that people live in — you are designing for people, not machines.

That you have a stake in magic and mystery and art.

That sometimes we fall back on Rousseau and separate mind from body.

That you understand the value of pictures, words, and critical thinking.

That poetry drives you, not hardware.

That you are willing to risk, make mistakes, and learn from failure.

That you develop a practice founded in critical reflection.

That you build a bridge between theory and practice.

That you embrace the unexpected.

That you value serendipity.

That you reinvent and re-imagine.

That you listen. That you ask questions. That you speculate and experiment.

That you play. That you are spontaneous. That you collaborate.

That you welcome students from other parts of the world and understand we don’t live in a monolithic world.

That each day is magic for you.

That you turn your thinking upside down.

That you make whole pieces out of disparate parts.

That you find what makes the difference.

That your curiosity knows no bounds.

That you understand what looks easy is hard.

That you imagine and re-imagine.

That you develop a moral compass.

That you welcome loners, cellists, and poets.

That you are flexible. That you are open.

That you can laugh at yourself. That you are kind.

That you consider why natural phenomena seduce us.

That you engage and have a wonderful time.

That this will be two years for you to expand — take advantage of it.

Appolinaire said: — Come to the edge, — It’s too high, — Come to the edge, — We might fall, — Come to the edge, — And he pushed them and they flew.